Finding Your Inner Mickey Mouse: Working the Male Falsetto

The use of the falsetto range is a huge benefit for male[i] singers. Unfortunately many choral directors and voice teachers do not know how to speak to singers about the use of falsetto, let alone work with them to expand control of the register. Female directors and directors with mostly instrumental backgrounds are at a particular disadvantage, the former due to the physiological differences between the male and female voices, and the latter due to potential lack of training or experience with singers in general. The issue is complicated by the fact that the singers themselves rarely understand the physicality of this range of their voice. Working with vocalists of all ages over the past several years as a voice teacher, choral singer, and choral director I have developed a series of exercises aimed at giving male singers more of an understanding of and control over their falsetto.

It is clear to anyone who deals with a recently changed male voice that the drop caused by puberty is a kind of vocal trauma. Oftentimes singers who had no issues with pitch while they were a soprano or alto suddenly have issues matching in the tenor or bass range, and consequently, the newly developed falsetto. Singers should focus on gaining a certain amount of control in this register as soon as possible.

Clarification of Terminology

Due to the lack of standard terminology in voice teaching, especially in regards to vocal registers, I think it helpful to clarify for the purposes of this post. I will be using the range classifications described by James C. McKinney in his book The Diagnosis and Correction of Vocal Faults. I believe this will be the clearest terminology to use for the subjects discussed below. The modal register is “the normal register for speaking and singing,”[ii] commonly referred to by many people as the “full voice.” The falsetto range lies above the modal voice, and as discussed below, overlaps it slightly.[iii]

While the notes of these exercises are standard warmups that can be done by any vocalist, the specific methods described are targeted for male vocalists whose voices have changed. Therefore, unless explicitly stated otherwise, the use of the word “singer” refers to those changed male voices.

Choral Uses of Falsetto

The most obvious use of falsetto is for notes that are too high for the modal voice. The wide variety of vocal ranges in every choir, regardless of age or technical level, can make matching these high notes a problem, with both tenors and basses. The use of falsetto can help with this. In order for it to be effective however, the singers must understand how to switch effectively between the modal and falsetto ranges, or vocal cracks may be audible.

Falsetto development is also good for overall vocal health. With a good falsetto the singer can “mark” any high passages in rehearsals, saving voice for performance or general health purposes. This can be particularly useful when working passages of music with a high tessitura. The strengthening of the falsetto range will also help to strengthen the other ranges of the voice. The navigation of the modal/falsetto switch that comes with the exercises below can also help singers with breaks between other registers.

Owing to the very specific timbre of the male falsetto it is often useful for choral directors to experiment with passages being sung in the falsetto range for sake of musical interpretation. Singers often develop an ego about the notes they can hit and will go for a high note with a force and tone that may be inappropriate for the given passage. This is sometimes completely unintentional. It is the choral director’s job to deliver the musical interpretation and to tell the singers the best way to do so. A mutual understanding of falsetto can help the director and their choir to find the exact musical interpretation for those higher, quieter passages.

Falsetto can be incredibly useful as a device to communicate phrasing and musicality. A prime example is contained in Eric Whitacre’s Go Lovely Rose (Figure A). The chord in measure twenty-six has all four voice parts holding a unison C#4 at a pianissimo dynamic, on the word “small.” While this note should not be extremely high for any well-developed bass/baritone, the fact that the whole choir is in unison on a pianissimo can lead to the basses being overbalanced if using the modal voice. Falsetto is an easy means to remedy this balance issue[iv]. None of this is possible if the singers and the director do not understand how to utilize the falsetto.

Figure A: Go Lovely Rose, Eric Whitacre

Stigmas of Falsetto

Choral directors should note that many adolescent males may have an inherent stigma about the falsetto range. Oftentimes this comes from them not wanting to sound like women. It is the same reason many adolescent basses will modify their sound to an overly dark tone that they think is more “manly.”[v] This is a societal issue that can be dealt with in the choral classroom. One technique that I have found incredibly useful is to discuss the number of pop stars that use falsetto. While people like Adam Levine of Maroon 5, Sam Smith, and the like may not always be good role models of vocal technique, pointing them out in this instance is often helpful in combating some of the stigma attached to the falsetto.

Singers may also be worried about the sounds the voice often makes when it “cracks” into or out of falsetto. Many are embarrassed by these noises that come naturally with the growth into adolescence and continues into adulthood. This should be addressed by pointing out that it happens to all changing voices. Male choral directors may even want to intentionally crack during rehearsal to model this. It may be helpful to note that the control granted through the use of these exercises can decrease the instances of said cracks while singing.

Neither of these conversations can be a one rehearsal fix. It needs to be a continuing conversation to get the singers acclimated to the ideas. If the falsetto is simply introduced as a useful aspect of the instrument that, while helpful, has these natural tendencies, and separated out from the personal identity of the singer, that can go a long way toward eliminating the aforementioned stigma and allowing the work to begin.

Goals of Falsetto Technique

Even with years of study the falsetto will have its characteristic “airy” quality, due to the fact that the degree of glottal closure in falsetto is much less than in the modal register[vi], and the lack of overtones[vii]. It is unrealistic to expect the tone quality of the falsetto to match that of the developed modal voice. There are male altos and countertenors who have a modal voice quality in that pitch range, but they are the exception rather than the norm. For the general population of male singers the goal should be to develop the ability to switch between the modal voice and the falsetto as effortlessly as possible. Most singers begin with an interval of a third to a fifth where the two ranges overlap, generally in the area of C4. Once the voice is more trained and developed this should extend to approximately an octave’s worth of overlapping pitches. I have had singers get as low as D3 in the falsetto range. The lower of these overlapping notes will not really be practically used in the falsetto range, but their existence is a sign of good vocal health and development. The goal of vocal study, and that of the exercises that follow, is to allow the singer to attain the control necessary to switch between the modal and falsetto ranges on any of these overlapping pitches, as well as to modify the quality of both registers to make the transition between them sound as smooth as possible.

Implementation of Exercises

The exercises below should be introduced as part of the regular warmup routine. The director should not do the entire sequence in one rehearsal. They are designed to build upon each other over a series of rehearsals or lessons. Part of this is due to the fact that extended amounts of time working the falsetto can tire out the entire voice and lead to damage if done for too long. This is especially true in situations where there is a great deal of crossing from the modal voice to falsetto.

The ideal setting to implement these exercises would be in a men’s choir rehearsal or a men’s sectional. In a mixed choral setting it is possible to have the sopranos and altos do the same exercises at the same pitch as the tenors and basses. It could even help the men match pitch. If this is the only option to teach the exercises the men should be given a few iterations of each exercise on their own as well.

If it is possible to work with the men alone the separation of tenors and basses could be of use once the first few exercises have been mastered and the majority of singers feel comfortable. At that point the separation of the two voice parts could lead to more detailed work with the specific sets of pitches used. However, this is not necessary for the full development of falsetto technique. It will also depend upon the age of the singers the director is working with. High school boys have voices that are usually not at all settled yet, so the separation of tenors and basses may be of no benefit at all. But if working with college upperclassmen with more developed voices and defined ranges it could be useful as a very low bass and a very high tenor may have distant breaks in their voices.

Like any other aspect of musical technique, different students will progress at different rates. This is one more reason to stretch the exercises over a long period of time. The director is encouraged to spend at least a week on each step detailed below before moving on. This assumes the five daily rehearsals typical of many secondary school choral programs.

As a special note for female choral directors; most of the time male singers will try to match the timbre of the pitches given. Experienced female directors working with male singers may have noticed that if they sing the pitch in the male octave the singers inevitably go down another octave. This phenomenon does not generally happen in the falsetto. Once the feeling is established and slightly comfortable the singers usually have no trouble matching female singers at pitch in the falsetto range.

The Exercises

Throughout these exercises emphasis should be placed on noticing how the vocal mechanism feels. When working this in the context of private vocal lessons, you can of course spend all the time you need on each step to ensure the student is comfortable before moving on. In a choral setting, particularly a secondary classroom, you should wait until the singers are all at least familiar with the switches described in each step. Notice the use of the word “familiar” instead of “comfortable.” Not all of the singers will feel comfortable with the transition at each step of the process. It is up to you as the director to determine when to move on and how to best help the singers that may be behind the others.

Step 1: Feeling of Familiarity

Vocal slides/sirens are often the easiest way to get the singers used to feeling the vocal mechanism, in whatever vocal range. It is often easiest to have the singers start in falsetto and slide down into the modal voice. Some singers will have a problem even getting into the falsetto. There are several tricks that can help. Referencing the voices of cartoon characters such as Mickey Mouse, or the voice used to imitate women or girls is often the most effective. Having a more advanced singer demonstrate the falsetto sound and the switch is an invaluable tool as well. Some singers will actually have more success sliding from the bottom of the modal voice up into the falsetto, while others will fight and stop when they feel the vocal cords begin to make the switch.

Slides should eventually be used in both directions, with emphasis being placed on the feel of the switch between registers. Use of the word “flip” is often a good way to help visualize the change, and can really influence the ease with which that occurs.

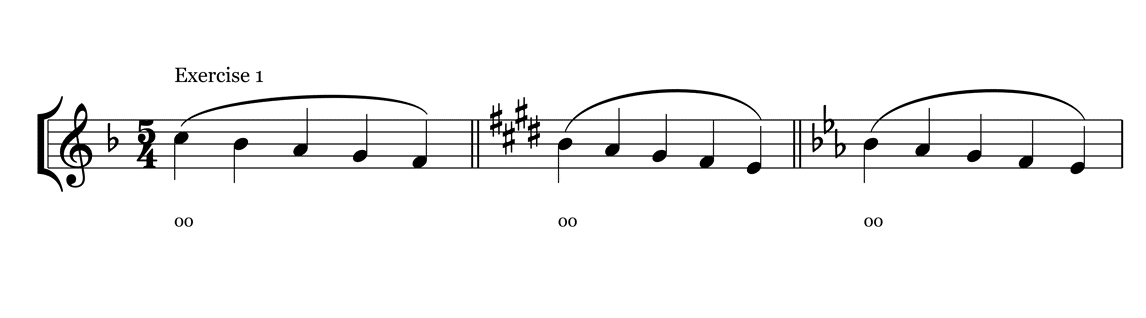

Once the slides are progressing, Exercise 1 should be used to start getting the singers used to changing pitches in falsetto. Starting around C5, an [u] vowel is particularly effective to help focus the sound. The singers should not fight the voice when it breaks into the modal range at this stage. The exercise should continue downward by half steps until all the singers are in the modal register.

Step 2: Extremes

Once the singers have gotten used to the slides and descending steps we move on to two exercises that begin to work a controlled switch between the registers.

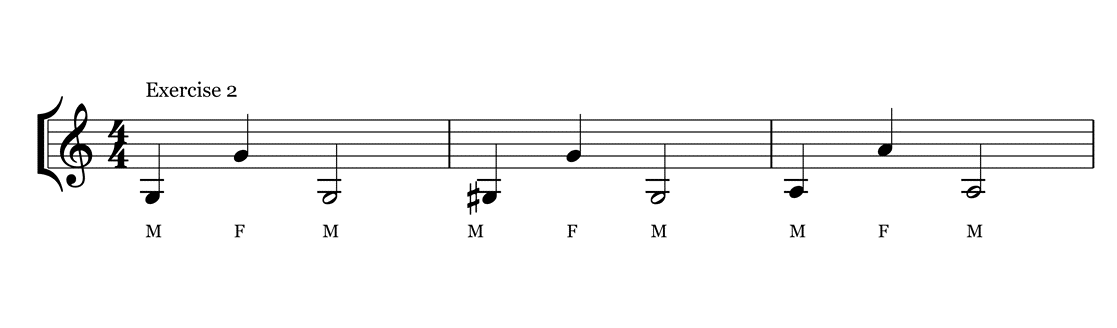

In Exercise 2 we jump octaves, the bottom note in modal and the top in falsetto. The interval of an octave is crucial. When coming down from the falsetto to the modal range the voice naturally wants to jump about a 4th as it breaks or cracks. This is likely noticeable when doing Exercise 1. The octave is far enough to make the switch while avoiding this problem that comes with that natural change in registers. Eventually the interval can be narrowed, though I suggest going no smaller than a 5th at this stage. This is not only a good way to also incorporate ear training but forces the singers to begin controlling the change more and more as the interval size decreases.

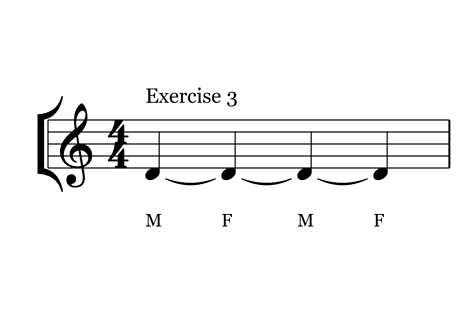

While working Exercise 2 for distance the other extreme should be explored. In Exercise 3 pick a pitch that most of the singers can overlap. Between C4 and E4 is usually what works best. Then have the singers sing that pitch but flip between modal and falsetto. This may not be easy for most singers initially, and changes of pitch will be heard. The goal is to minimize and control the tendency for the pitch to change. This is also a great chance to really concentrate on the physicality of the register change. Have them pay close attention to and describe how it feels in the body as they go back and forth. Noting what their own personal tendencies are will be helpful moving forward.

Step 3: Skip

Once the singers are familiar with the switch between registers we can begin to really work the versatility of the transition. At this point I want the singers to be able to do Exercise 2 with the interval of a 5th fairly consistently. Again, I point out use of the word “familiar” rather than “comfortable.”

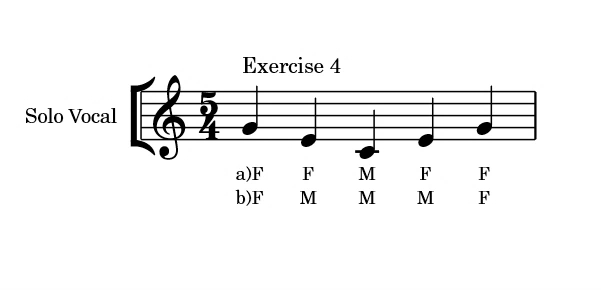

The singers should already be familiar with singing in falsetto and breaking down into modal voice from Exercise 1. It is usually much easier to come down out of falsetto than move up into it, at least initially. Now we will begin working control of the switch. Whereas Exercise 1 lets the singers break wherever they are that day, Exercise 4 has a more specific goal in mind. Exercise 4 should be done in two ways.

First sing down in falsetto and switch to modal voice on the bottom note. This may need to be done very slowly so the singers can really feel their way through the switch. Again we are working with intervals larger than a step because the transition from falsetto to modal and vice versa in stepwise motion takes a great deal of control, and we are building up to that. Some singers may be able to go there right away, but they should still follow this step, as it will only provide them more information on how their voice behaves. Eventually move on to 4b, where only the top note is in falsetto.

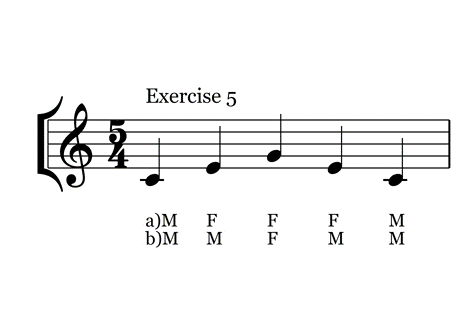

Once the singers have become accustomed to Exercise 4 we reverse the pattern, moving from the modal to the falsetto. Start with Exercise 5 and have the singers sing the lowest pitch in full voice and the top two in falsetto. After a couple of rehearsals doing that, change it so that only the top note is in falsetto.

It does seem a bit counterintuitive to do it in this order, but through much experimentation with a variety of singers I found that the longer the voice is in falsetto the easier the exercise is. Since we are going for a gradual increase in control this is exactly what we want and should always be kept in mind as we move forward. The exact order of operations can change from student to student. With some singers I will begin working Exercise 5a at the same time as Exercise 4b. Others I will do one or the other first, then move to the next. Sometimes I will think moving on to 5a first is the right move, try it, and it proves rather difficult for the singer. It depends on the singer/choir. The thing that should not change is that both variations of Exercises 4 and 5 should be consistently successful before moving on to the next step.

Step 4: Steps

Once the singers are doing well with Exercises 4 and 5 we can progress to stepwise changes. This is incredibly relevant because in vocal literature we often have to make the register switch on a stepwise run of notes. If the singers are unfamiliar with the technique and/or do not prepare the transition we can get undesirable cracks in a performance.

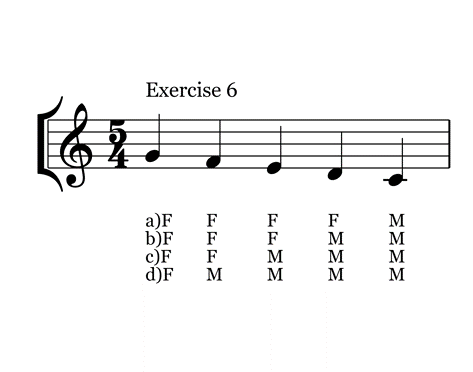

We begin with the same five note descending pattern as Exercise 1, only now we are going to plan exactly which note to change on. The first few iterations should have the change occur on the bottom note, making that the only one in modal voice. Then over the next few rehearsals/lessons it should be moved up note by note until only the top note is falsetto.

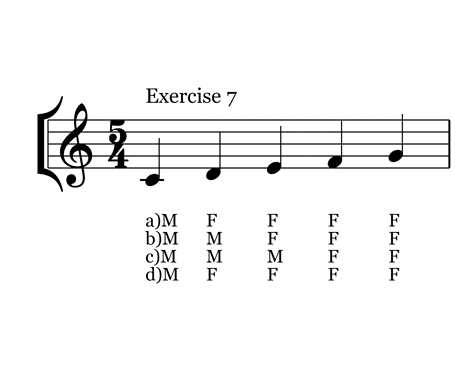

Exercise 7 can be introduced just afterward with the same objective. Start ascending with the initial note in modal voice and move up until only the top note is in falsetto.

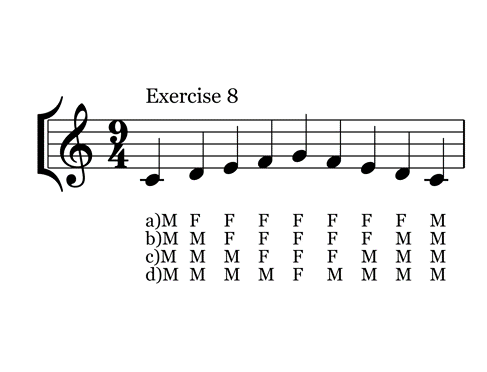

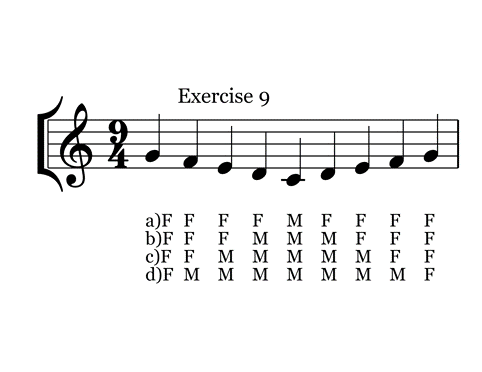

At this point the singers should feel confident in their level of control and can now move into Exercises 8 and 9. The objective should be the same, pick the pivot note and change it around.

Step 5: Expertise

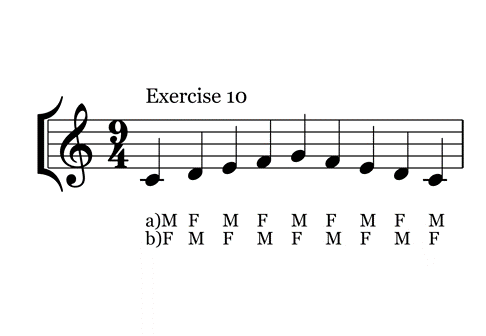

After working through these previous steps in the course of several weeks or months worth of lessons/rehearsals, the singers should be equipped to maneuver through the register transition in any number of contexts, but if the director feels it appropriate they can go one step further. Mastery of Exercise 10 will ensure that the students have total control, but it is not an easy exercise. The director may wish to leave it out with all but the most advanced students. Exercise 10 involves changing the register on every other note.

Some teachers might call this overkill, but to draw a sports parallel, shooting baskets from the three point line makes free throws much easier. If the singer can successfully navigate this exercise they should be able to handle anything the vocal repertoire throws at them.

Conclusion

Many choral directors never even mention the falsetto range in rehearsals. The ones that do often throw it at their singers without any of them really knowing what to do about it. It is to the advantage of both the singer and choral director to have a well-trained falsetto. If the above sequence is carefully followed there is no way that the singers will not gain such control, adding to their versatility as choral singers.

[i] In this post I will use the term “male singers,” counter to some of the ideas presented in this post. The majority of the singers this post will apply to are people who will identify as male, with voices that have dropped as a result of puberty. While most of these singers will be cisgender men who experience that in the teen years, I don’t wish to discount the experience of trans men who experience this shift later in life or nonbinary singers who experience it at any point. In the case of this post “male singer” is used for efficiency, to distinguish from those singers who have not experienced the lengthening of the vocal cords (traditionally female), as the falsetto range behaves much differently for those singers.

[ii] (McKinney, 1994, 2005)

[iii] (McKinney, 1994, 2005)

[iv] (McKinney, 1994, 2005)

[v] (Dehning, 2003)

[vi] (Miller, 2004)

[vii] (McKinney, 1994, 2005)

Dehning, W. (2003). Chorus Confidential: Decoding the Secret of the Choral Art. Pavane Publishing.

McKinney, J. C. (1994, 2005). The Diagnosis and Correction of Vocal Faults: A Manual for Teachers of Singing & for Choir Directors. Long Grove, Illinois: Waveland Press, Inc.

Miller, R. (2004). Solutions for Singers: Tools for Teachers and Performers. New York: Oxford University Press.