The Ear and It's Muscles: Ear Training for Vocalists

Ear training is extremely crucial for all musicians. The ability to sing and play in tune is necessary if we are to collaborate with others at all. Each instrumentalist has their own particular challenges when it comes to intonation, but since the vocalist is their own instrument it is particularly important for them to pay special attention to ear training. It is something I make a priority in my work with my voice students and ensembles.

My biggest focus is on the physicality. Many singers don’t realize how much ear training is really about the physical mechanisms and muscles in the throat and abdomen. I demonstrate this with a bit of a parlor trick. I am able to pull a C-sharp out of the air, sometimes I’m a little sharp or flat, but it’s always a C-sharp. I point out to them that I do it on a very specific vowel. I can do this because a piece I sang on my senior recital started on that note and the word was the German “Ihn,” and I remember how that feels. This is the best example I can give of how important muscle memory is in ear training. I have noticed that a lot of the people that would be called tone deaf because they cannot match pitch are not having an issue with their hearing, but with the physicality of the vocal mechanism. Slides are a great way to start with these students. Getting them to feel the changes in the pitches as they move up and down can help them begin to get a sense of how to match the pitches they hear.

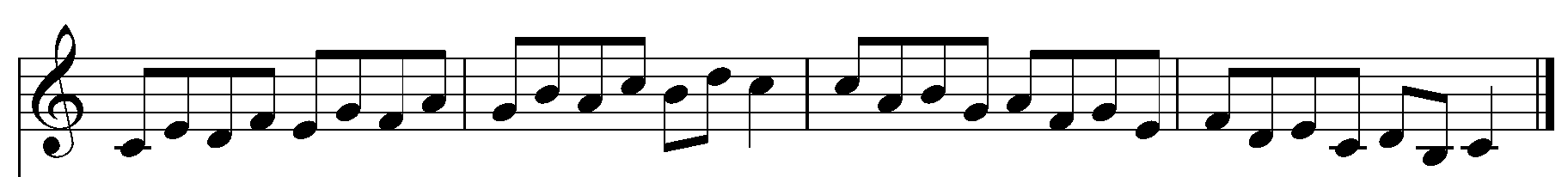

Once the vocalist is confidently able to match single pitches I begin a program that evolved out of the ear training work I did myself in college. The starting point is a simple major scale (Figure 1).

Figure 1

I insist on solfege for two reasons. First, the vowels of the syllables are the pure vowels we work in vocal music. Secondly, because the relationship between those syllables can be just as helpful as muscle memory. I always compare the solfege syllables to the fingers used by instrumentalists. After years of working as a violinist my hand knows what the Perfect Fourth between my 1st and 4th fingers feels like for example. Working the solfege syllables creates similar connections. We may have difficulty with the abstractions of something like G-flat to C-flat, but if we know that it’s just Do to Fa in the key of G-flat, that can be helpful. Once the scale is comfortable I begin working what I call an intervallic scale (Figure 2).

Figure 2

This exercise works some of the most common intervals. I make the students focus on the feeling of the intervals. Doing this in multiple keys helps to emphasize that the intervals are the same distance even when the notes change (i.e.: a major sixth between A and F-sharp should feel and sound similar to a major sixth between C and A[1]). Some good things to do, especially when first working this is of course to go slow, but also add slides between the intervals. When this is done it can help the student hear when they reach the pitch and how it feels. When this is done it should be emphasized that it is only for the exercise and that outside of this, precision should be used in getting from one note to the next.

From there I take two branches. They divide by my simple definitions of melody and harmony I use when talking about music theory; melody is horizontal pitch, focusing on getting from one note to the next, while harmony is vertical pitch, focused on training intervals with another instrument or singer. First we go melodic by working patterns of specific intervals. This starts with an exercise that is familiar to many people, a scale in thirds (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Working this in multiple keys is good to do for the same reason as the intervallic scale – to emphasize that the size of the interval should sound and feel similar regardless of the notes. Many people do these scales in thirds because it is such a common pattern. Along this branch I go a few steps further by doing the scales with all of the diatonic intervals[2]. Fourths (Figure 4) and fifths are the next step.

Figure 4

With intervals above a fifth we often have to make adjustments for the range. This usually involves doing sixths (Figure 5), sevenths, and octaves in one key on the ascent, and in a different key on the descent.

Figure 5

For the harmonic route we do parallel scales. I again start with thirds. The initial way this works is by having the student sing the major scale while I play a third above or below on the piano (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Doing this I have noticed an interesting phenomenon. It is not a hard rule but people who sing soprano or tenor tend to have an easier time when I am playing a third below, and altos and basses an easier time when I play the third above. For many students it doesn’t matter, but it is enough of a trend to be notable. I will work the interval both above and below for a bit. I keep it diatonic, so I am actually playing a mode in parallel to the major scale the student is singing. The next step is for me to sing the mode instead of just playing it on the piano. At this point many students have a more difficult time and actually begin singing with me instead of sticking to the scale. This is because they are now hearing the parallel pitch in a matching timbre of a voice so they often try to match that. It is a crucial step, especially if the student is going to sing ensemble pieces. Around the time we move on to that step, I will add one of two things. Both will be done eventually, which I do first depends on the student. I will either move on to a new interval (sixths due to their relationship with thirds, then fourths/fifths, and finally sevenths/seconds), or I will have the student sing the mode while I play or sing the major scale (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Doing both of these things will ensure they have a good ear and ability to sing in tune. When a vocalist can sing a scale a second away from the one they are harmonizing with, most ensemble work will seem easy in comparison.

The time investment here does not have to be dramatic. I tend to think of these exercises the same way I do scales, arpeggios, and other short exercise for my instrumental students, working on them for five to ten minutes of a half hour lesson, and gradually moving through all of the steps outlined over a long period. I find it is extremely worth it for students to be able to more solidly move their way through any literature they come across.

[1] The range of the notes will be a small consideration here. As the extreme ends of the vocal range are approached the feelings may shift slightly, but this is more a function of the structures around supporting the tone and not ear training in and of itself. For the purposes of ear training, especially in the early stages, the exercises should be kept at a midpoint in the vocal ranges the students are working.

[2] It is possible to do these scales strictly by the interval, i.e.: all major thirds, rather than going diatonically, but that is something I save for much more advanced levels of ear training.