One Step at a Time: A Sequence for Learning Vocal Music

Words are the main thing that sets vocal and instrumental music apart from one another. The text adds many layers to the music both in meaning and technically. They can serve as a guide in interpretation and phrasing. The vowels can affect how we sing a note, and how we breathe. Consonants cause all sorts of issues across musical categories. Because the text is so important it makes sense to use it as the focus of learning the music.

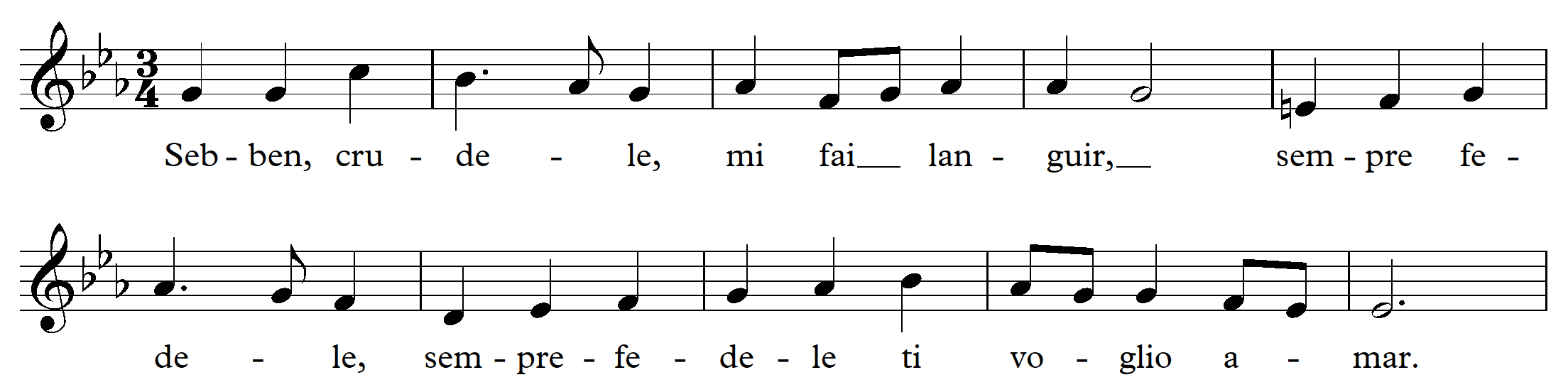

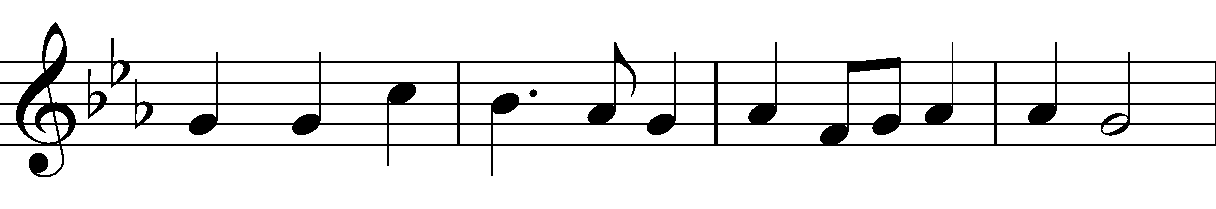

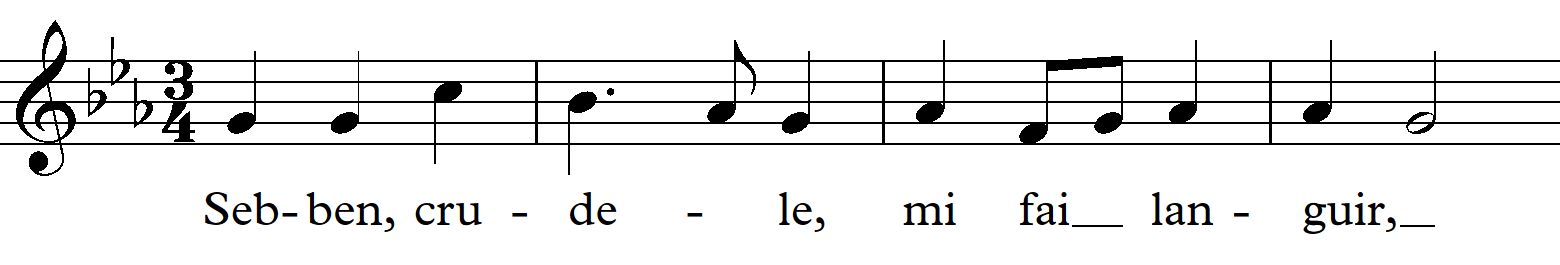

One of my college choral professors walked me through a sequence to help quickly drill and memorize vocal music. It is a very good process that I like as both a student and a teacher, mainly because it builds up the music step by step, adding one thing at a time beginning with the text. I will use the first two phrases of “Sebben Crudele” by Antonio Caldara (Figure 1) to illustrate the process.

Figure 1

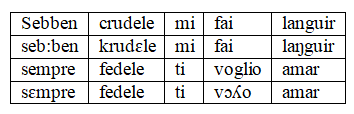

Ideally I like to prepare by writing out the text a couple of times with specific goals. First I will write the text and an IPA pronunciation guide underneath it (Figure 2).

Figure 2

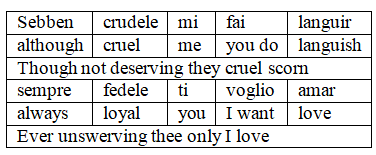

I do this regardless of the language I am working in, because it starts the cementing of the text in preparation for memorization. Then if the text is in a language other than English I will write out two translations; a literal word by word one, and a poetic one, which is often included in the music itself (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Having both of them can be incredibly helpful in knowing which words are really where the emphasis should be in phrasing. There have been times when I have had to learn a piece in a very short amount of time so I have skipped these steps, but I always find them helpful in the long run.

Once that is done it is good to go through the piece and decide how large the chunks you drill are going to be. It is better to start small at the beginning, one phrase at a time usually being the easiest. This is another place where the text can be very helpful – look for the punctuation. If you prepared the text as described in the last paragraph you’ll likely already have a good idea of the phrases to be drilled, but the music itself can present changes that aren’t inherent just in the text. A section of the text could be repeated with different music, or a complicated melody could shorten the length of a chunk you want to drill by a few words. Each piece will present different challenges. Once the chunks you will drill have been identified and marked, you’re ready to go through the steps of the process. To be most effective be sure to repeat each one at least three times.

The first step is to simply speak the text to get the pronunciation of the words in your mouth. Eliminate the rhythm entirely and just be sure you can practically pronounce each word in the sentence. If the language is one you are fluent in, and the sentence isn’t complicated to speak this step can be skipped. Tempo should be a consideration here as well, because something that is sung in a slow tempo may be no issue, but a fast tempo could be quite the challenge. This step is particularly crucial for foreign languages that are less familiar to you, and will make the IPA pronunciation done earlier come in handy.

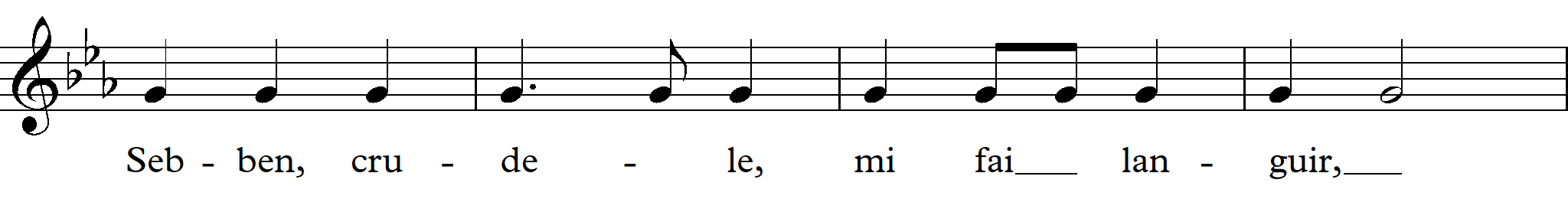

Next is to speak the text in the rhythm used in the piece (Figure 4).

Figure 4

This begins to give you a sense of how things will eventually need to be phrased, and can reveal potential issues. Are you lingering on any consonants that might cause pitch issues later? Is the text set in a way that seems to counter the natural emphasis of the rhythm? Are there any complicated rhythms that perhaps need to be isolated further? Again, tempo can be a massive consideration at this step. If you skipped the speaking because you are fluent in the language, do not skip this step. The rhythm could cause a multitude of complications. To most effectively learn the piece this step should be done regardless of familiarity with the text or language.

Next you move on to singing, but only on a single pitch. Keep the text and rhythm from the previous step, just add pitch now (Figure 5).

Figure 5

This can begin to really help you map out how you use your air and when you might need to breathe. You can choose any pitch for this but some options are better than others. I will most often go with whatever note the phrase starts on. The tonic pitch of the key can be good too. Perhaps the best option is to pick a pitch that is basically the average tessitura of the phrase, as this will allow you to do the work within the proper part of your range. All singers quickly learn that the way you sing something in the lower part of your range might not be the way you’d sing the same text/rhythm an octave higher. Whatever choice is made, the key is to stay on that single pitch for the whole phrase.

The next step is where you add the written pitches (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Ideally this will be done with a piano or similar instrument, though any pitch source and/or solfege can suffice. I will typically play the notes without singing them three times to internalize the pitches, then sing as I play three times.

Then the final step is to sing the phrase as written with all the pitches and rhythms acapella (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Most of the time it will be easy for the singer at this point given all of the drilling that has been done previously. If the phrase is particularly challenging in terms of pitch some intermediate steps can be made. You could play the chords that are occurring to give harmonic support, or simply play notes to check in as you go, maybe the first note of each measure, or the second note of a tricky interval. Slowly strip those away until you can sing the phrase correctly acapella. That will ensure you have a good grasp of the piece.

Once this process is done with every phrase, the piece is usually pretty solid. One thing that can happen though is that the transitions between the phrases you drilled can be shaky. So I will usually repeat the process, but widen it to do two of my original chunks at a time. So I would repeat the whole process with chunks one and two, then with two and three. I will often start at the end and work my way backward for this second round. Even though we are now doing longer chunks the process almost always goes faster because we know the individual phrases. Doing this second round is also very helpful in the memorization process.

Of course not all phrases are created equally, and the amount of time required in this process will vary based on your skill level. Experienced sightreaders may only need to follow this process for a few phrases in a piece, though I would argue that going through at least one time in each step can be beneficial for even easy phrases. And there will be other times when many more than three repetitions will be required to feel comfortable with a given step. As a general framework though, these steps can serve very well as the basis for a vocalist’s practice of literature.