Secondary Minor Scales - Upper String Scale Series #10

Once the student can comfortably play all three forms of the primary minor scales I will begin work on the secondary minors. The process is very similar to the one described for the secondary majors; I work my way up the fingerboard, transposing the primary scales up or down as necessary. I introduce all three forms at once, key by key. These scales may be the first time that students will come across the double sharp, so they must be prepared for that as well.

We begin with the first finger E-flat Minor (Figure 1). I will always have the student play the natural version first, which form comes next depends on each student. If they have a good grasp of the scale degree idea I will have them raise the seventh for harmonic, then move on to the melodic. If they are a student who works better with the finger patterns I will have them change the color for the melodic first, then move on to the harmonic. In this instance I will try to eventually guide them to thinking of the natural-harmonic-melodic order, as it does make more sense from a music theory standpoint, but as long as they are playing the three forms properly I don’t care too much about the order. This continues on to the B-flat and A-flat, and A-sharp Minors (Figures 2, 3, and 4).

From there come the F and B-flat second fingers (Figures 5 and 6). It is worth reminding the student of enharmonic scales with A-sharp and B-flat. The two octave B-flat should be covered here as well (Figure 7).

The third finger C-sharp and G-sharp are next (Figures 8 and 9). Those are both fairly straightforward following the same process of transposing the primary scale.

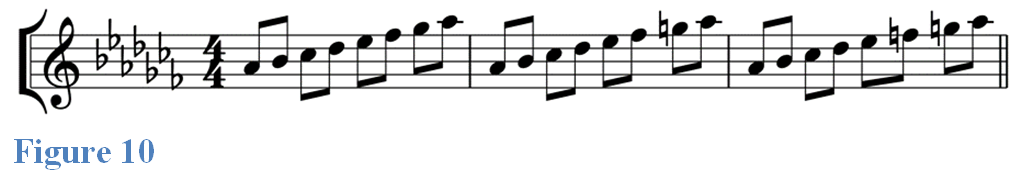

The fourth finger scales begin by examining the enharmonic relationship between G-sharp and A-flat (Figure 9 and 10). I will then go over the two octave A-flat Minors (Figure 13) before moving on to D-sharp (Figure 12). I will compare it with its enharmonic E-Flat Minor. This is the first time we’ve had enharmonic scales begin on different strings because the D-sharp starts with the fourth finger, and E-flat with the first, but the procedure for comparison is the same. Once that is done we’ll move on to the high octave of A-sharp (Figure 13). For theory purposes I will usually have the student work the enharmonic relationship between two octave A-sharp (Figure 14) and B-flat Minor (Figure 7).

Once I have done these I take them to the low octave G-sharp (Figure 15), which is related to these scales. We have already discussed its enharmonic A-flat Minor, but G-sharp is the key we are more likely to see in literature, so it is good to cover this lower octave as well. The A-flat should be used to get the pitches into the ear, as well as offer the alternative fingerings that will help in repertoire, as G-sharp is complicated by the tonic pitch requiring a lowered first finger. In the case of literature I would suggest going with whatever fingering gives the best and most efficient tuning, but I teach the G-sharp Minor scales themselves with a slide on the second finger between the A-sharp and the B. This allows the rest of the scale to be thought of in the patterns used for the primary G Minor scales, and also prepares for the two octave G-sharp Minors by allowing a seamless transition into the higher octave we drilled earlier. I went with the 2-2 slide rather than a 1-1 between G-sharp and A-sharp because that is the fingering that is used for the three octave scale in the Flesch scale system, which are the fingerings I myself use when drilling scales and the ones I teach to my advanced students. Since it fits well with the finger pattern process I saw no need to reinvent the wheel. The student can then put this low octave together with the higher octave to do the two octave G-sharp Minor scales (Figure 16). Once again, a comparison of the enharmonic (figure 10) is good to do here.

Upon completion of this process the student will be able to play every scale that is possible in first position. These skills will not only transfer into higher positions in the study of two and three octave scales, but will open up possibilities in repertoire. Going through this system will allow the student to see patterns and possible fingerings in every key on the Circle of Fifths that may not have been thought of otherwise. This understanding of the fingerboard makes the player more versatile and better prepared to handle repertoire.