One Step at a Time: A Reading Sequence for Beginners

Note reading is one of the trickiest things to teach beginning string players. Many people are intimidated by music notation in general before they even pick up an instrument because it looks like a strange and complicated set of hieroglyphs. Add this to the fact that the beginning string player has to learn how to coordinate the completely separate processes of the left and right hands and it can become very complicated. This is why so many methods, including the famous Suzuki method, focus so much on rote learning at the beginning of a student’s career.

I start my students reading work right from the beginning – but I separate it from the work of the left and right hands in a process similar to that detailed in Chapter 1 of “Teaching Music Through Performance in Orchestra, Volume 2.” This is done over many lessons, while I am also working concepts of the left and right hands by rote. Then I slowly begin to combine reading with each hand on its own. When I work the reading I use a sequence of steps I’ve developed that help immensely.

Speak the note names out of tempo, including accidentals. This helps the student to figure out exactly what the notes are, since there is a big difference between F and F-sharp.

Speak the note names in tempo – no sharps or flats here. Leaving out the accidentals in this step helps the students maintain the proper rhythm and tempo, but I always make sure they are aware of the accidentals any time we do this sort of work.

Speak the finger numbers out of tempo.

Speak the finger numbers in tempo.

Speak and “air violin” touching the appropriate finger to the thumb to simulate the fingerboard. This is also a good way for students to practice without the instrument. Both note names and finger numbers should be used.

Speak and “silent violin” – the student plays the passage on the instrument but with no involvement of the right hand, no bowing or pizzicato.

Play the passage pizzicato (once the student reaches a certain level of confidence with and coordination of the bow I may skip the pizzicato completely).

Bow the passage.

These steps are useful in helping the student figure out which of the dots on the staff go with what finger in what spot on their instrument. This layering process helps them to build their skills slowly and avoid frustration. I find speaking the note names out loud is one of the biggest benefits, and allows students to quickly learn to read the notes without resorting to writing the names on their music.

I initially start this with the Finger Pattern exercise from Fingerboard Geography and the D Major Scale. Because both of these use stepwise motion I will use the actual notation for them. As we work that I will add in some simple pieces with a chart system I use instead of the music notation. These charts help to get the student prepared for pieces without a lot of stepwise motion.

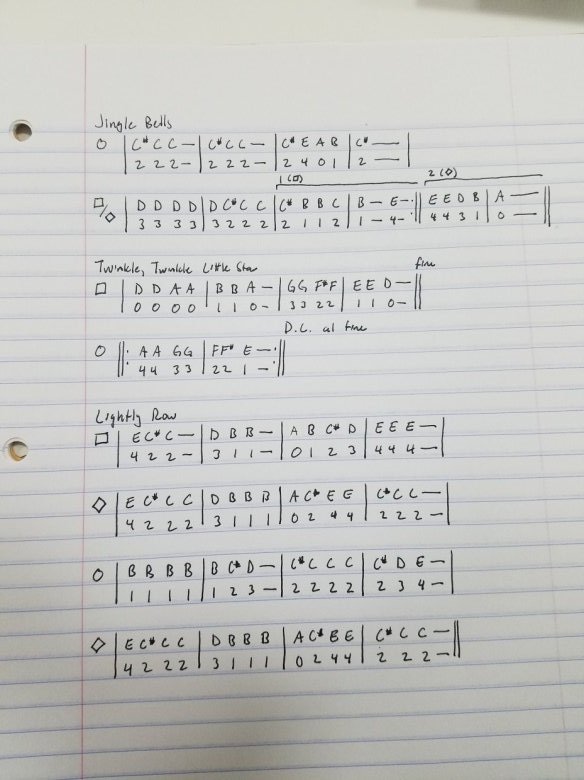

The first song I teach is Jingle Bells. I do this regardless of the time of year for a few different reasons: it is playable on one string, isn’t very difficult, and almost every student knows what it should sound like. I begin by letting the student pick what string to play on. Let’s say they chose the A string. I then draw them out something that looks like this:

A chart for Jingle Bells

I handwrite this on a piece of paper for each student. A photo of my hand drawn charts will be at the end of this post. I am adamant that students not write note names or finger numbers over every note in their written music. On these charts I do it for the purposes of cementing what notes go with what finger and to show the rhythm of each piece. They should have already been introduced to reading actual notation from the sequence with Barber’s finger pattern exercise and scales, but that is all stepwise. This prepares them to start reading pieces that move around with skips and leaps. I also use these charts to begin teaching the basic rules of music reading. I will draw a measure with four beats, using dashes to show notes that are longer than a single beat. I will draw accidentals on the first required note of each measure, but not the rest and explain the rule of accidentals carrying through the measure, and resetting at the bar line. I begin to discuss form as well, using shapes for the phrases instead of the traditional letters to keep from confusing the student about the pitches. I find that using form helps them to memorize because it allows them to think phrase by phrase, rather than note by note.

When I do this chart I will use it to train their ears as well. I will give them the first note on either my violin or the piano and play the first measure, asking them if the pitch changes. Then I play them the first and second measure, again asking if the pitch changes. For the third measure I go note by note, guiding them to the right pitches. I will ask them if the “mystery note” is higher or lower than the note before, then ask them to guess a letter. If they guess wrong I play them the pitch they guess, followed by the correct one so they can hear the difference. Once we reach the end of the first line I go back and have them fill in the finger numbers under the note name. This is also when I label it a circle (A) for the form, telling them that I’ll explain more about that after the second line. Then we return to our dictation game for the second line. Once we have figured out the notes and finger numbers for that I will have the student compare it to the circle, guiding them to see that it is completely different phrase, which I label the square (B). Then I draw a repeat and explain how it works. Throughout this process I encourage them to think of how the song goes, which is especially helpful with the next part.

After we establish that the circle/A section is repeated, I explain that the next line starts off like the square, so I play them the next line and have them identify where it changes. Once they do that we return to the dictation game and I draw the last two measures at the end of the square. Then I draw the first and second endings. I will explain that the last line is similar to our square but since it ends slightly differently we’re going to call it a diamond (B-prime). Depending on the student I may draw the diamond and the square instead of or next to the first and second endings. I explain that we play from the beginning and play the measures under the one first. Then we repeat, but since it’s the second time we skip the notes under the one and go to the notes under the two. Every student that I have done this with understands the concept in theory, but many of them have difficulty making the jump when put into practice. This is when I combine the reading sequence with the talk of form, drilling each phrase by itself and then the phrases together. I typically spend at least three lessons on this – covering one line per lesson.

Once the student masters Jingle Bells I move on to Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. I follow the same format I used above. I usually do it in D Major for violins and G Major for violas, as opposed to the Suzuki book’s use of A Major and D Major respectively, because I want to get them used to playing on those middle strings. Here is the chart for Twinkle:

Depending upon the student I may write out the full second and third lines, but most of them can handle the repeat and da Capo. I continue the form discussion here by labeling the first line a square and the second one a circle, then telling the student that Twinkle is a sandwich. Explaining it this way is usually what helps them understand the concept of the DC al fine. This is also when I explain the logic of using the open string versus a fourth finger. I point out that it makes sense to use an open string in the first measure because you have to play the first finger B right after, but a fourth finger makes more sense in measure five because using the open would mean crossing strings for a single note.

I do one final piece in this format; Lightly Row. The chart for that follows:

I write every line out for them like this because I use this piece to transition into the Suzuki books, having the student compare the charted song with the actual written music. From then on I use the Suzuki books for literature, supplementing with outside sources and exercises for technique. Between the work described in this post and my simultaneous work with the Finger Patterns [link], and the scales [link], the student usually has a good grasp of note reading, although I will still frequently use the eight step sequence with those Suzuki pieces when necessary to help coordination of the left arm and right hands. The key is to slowly layer all of the concepts while concurrently using some of the more traditional rote methods for playing technique.